Treated 2007 - Posted 2014 - Updated 2015

"We were so convinced that [proton therapy at Loma Linda] was the right course to take, that my wife joked, 'If you don't want to go there, I'm going to go alone and take your prostate with me!'"

Since my prostate cancer was diagnosed and successfully treated with proton radiation in 2007, I have talked to many other men suddenly confronted with the news that they have prostate cancer and should do something about it. As I was, they are shocked, scared, and anxious to "get rid of it" as quickly as possible. Like many others whose treatment has left them cancer-free, I try to give these anxious friends the most helpful guidance I can muster. I urge them to learn all they can about the disease and their treatment options, and of course I am happy to explain why I had opted for proton therapy.

Getting the Bad News: What to Do When You Learn you Have Prostate Cancer

Nearly a quarter of a million men in the United States are newly diagnosed with prostate cancer each year. They deserve the best and most appropriate treatment they can get. Instead, many rush to embrace treatment methods that may not be the best for them.

A 2010 AMA study showed that prostate cancer patients often opt for inappropriate or unnecessary treatment by practitioners touting their own specialties while disparaging or dismissing others. Furthermore, the psychological drive to get rid of the cancer as quickly as possible often leads patients to hasty decisions to embrace more drastic measures than their conditions warrant.

My own experience was typical.

For more than 20 years, my annual physical exam routinely included a PSA test and a digital examination of the prostate, a walnut-sized gland, essential to the reproductive process, lying deep inside the pelvic area. The test measures the level of an enzyme in the blood called Prostate Specific Antigen.

A rapidly rising PSA level may be a sign of potential cancer in the prostate. The test is not foolproof, and lately some specialists have felt the chances of false alarms, the fact that most prostate cancers grow slowly, and that there is are varying risks of unwanted side effects from current forms of treatment, mean its use should be cut back. In a controversial 2012 decision, the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that patients not be given the PSA test, a recommendation that many urologists and other specialists have chosen to ignore.

If PSA levels rise significantly over time, doctors routinely go to the next step - a biopsy: using a hollow needle device they take a series of threadlike samples from the prostate - as many as two dozen - which pathologists then examine to see if cancer cells are present. But if the USPSTF recommendations are followed religiously, there would be no biopsies. Some false positive results might be avoided, but some serious and fast-moving cancers might be missed. For this reason, urologists often conduct the PSA tests and biopsies anyway.

I'm glad mine did. A routine exam early in 2007 showed that while my PSA level was still fairly low, it had doubled in less than a year, so my urologist in Boston decided a biopsy was warranted. He performed it in April.

When he called to tell me that the biopsy was positive and I had cancer, I was devastated.

My first instinct was to get rid of the disease as quickly as possible, even if it would mean a lifetime of incontinence and impotence - the risks you may run if you have surgery (the so-called "gold standard" for prostate cancer treatment), or most other common ways to try to cure the cancer.

But unlike most newly-diagnosed cancer patients, I had good reason not to jump at the first chance to "get rid of it." My wife, Joy, had been going through a series of abdominal operations. There had been complications, and both of us felt I should not be making hasty decisions about my own treatment options until we knew she was out of the woods. We decided to make no decision until after July 1, when her last set of stitches would be taken out.

So I had time to learn more about my own case, the different options available, and to seek advice from a variety of specialists.

At my local library and through the Internet, I found endless books, articles, and web sites, all giving different and sometimes conflicting advice.

By far the most helpful and informative of the books I found turned out to be a paperback, You Can Beat Prostate Cancer, And You Don't Need Surgery to Do It, by Robert Marckini, a prostate cancer survivor (available at many bookstores and through Amazon and other web resources). His clear description of the disease and analysis of alternate therapies helped me to ask the right questions as I continued to look for answers, and ultimately to make what turned out to be the best possible decision for my treatment. I would urge anyone diagnosed with prostate cancer or concerned that he might someday have it, not to mention his wife or partner, to read this excellent book.

On the advice of a friend, I asked a medical oncologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital to assemble a team of specialists (a surgeon and a radiation oncologist) to examine me.

The surgeon agreed with my urologist that my age (I would soon be 74) meant that surgery could impose unnecessary risks. But the radiation oncologist seemed to go out of his way to irritate me. He chastised me for wasting his time with questions about information I had found on the Internet. "You lay people can't expect to understand all these details," he said.

And he dismissed my concerns about side effects, most prominently incontinence and impotence. He said he could get rid of my cancer (Wasn't that what I wanted?) with external beam x-ray radiation. Besides, he said, "almost everyone gets side effects." But then he told me that long-term side effects from radiation only affect some 2 to 3% of patients.

I was not reassured. I had no interest in wearing a diaper and having no sex for the rest of my life. When he and the surgeon left, the medical oncologist astonished me by saying, "That 2-3% number is just balogna. It's more like 40%."

His caustic remark was confirmed by an article in the American Medical Association publication Archives of Internal Medicine (March 8, 2010), which concluded:

Specialist visits relate strongly to prostate cancer treatment choices. . . [cancer] specialists prefer the modality they themselves deliver . . . . it is essential to ensure that men have access to balanced information before choosing a particular therapy for prostate cancer.

This bias, combined with a psychological drive to "get rid of" the cancer the fastest way possible, leads many newly diagnosed patients to unwise treatment decisions, quite often surgery. And even though I had been told that at my age surgery was not a good option, part of me was still reluctant to rule it out.

Confused by conflicting advice from doctors, I went to a prostate cancer support group meeting. There I was urged to learn all I could about my own case so I could explore my options with a better understanding of their consequences.

I also contacted other patients who had undergone the most frequently used therapies: surgery - conventional, laparoscopic and robotic; radiation, both external beam radiation and brachytherapy (radioactive seed implants); and "watchful waiting" -and found that many of them had developed distressing side-effects and wished they had tried something else.

But the patients who had experienced proton radiation therapy were almost uniformly pleased with the results. For many of them, the cancer was gone, and they often had no side effects whatever. In their case, a 2-3% incidence rate seemed more plausible.

Most of them had received their treatment at the James M. Slater, M.D. Proton Treatment and Research Center of Loma Linda University Medical Center in Southern California. Since 1990, this center has treated more than 15,000 cancer patients with protons in a 200-foot long facility built for the purpose. More than 10,000 of them were prostate cancer patients, most of whom returned home with their cancers cured, and with few if any side effects. The treatment is painless, non-invasive, and covered by Medicare and most insurance providers.

I live near Boston, where there are many fine medical institutions that can treat prostate cancer. One of them, Massachusetts General Hospital, is equipped to perform proton therapy, but a senior radiation oncologist there told me in 2007, that in more than 30 years they had only treated about 300 prostate patients.

At Loma Linda University Medical Center they had treated thirty times as many. The decision to have my cancer treated there with proton radiation was easy.

Proton Radiation: Maligned, Misunderstood, but Just Possibly the Most Effective Cure for Prostate Cancer

The magic behind proton radiation is the Bragg Peak.

Bragg Peak is not the name of a mountain, but of a remarkable physical principle, named for William Bragg, a British physicist who discovered it in 1903. It makes it possible for doctors to destroy cancer cells using proton beam radiation therapy.

Radiation, whether employing protons or conventional x-rays, destroys cancer cells by damaging their DNA so the cells cannot reproduce.

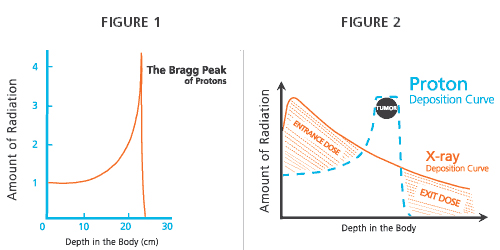

When x-rays (photons) pass through the human body, they destroy tissue from the moment they enter it until they pass out the other side, attacking healthy cells as well as cancerous ones. This is the case both with a single beam and with the more advanced Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT), in which multiple beams of conventional radiation are focused on the target area from different directions. While the radiation in each beam is of lower intensity than the single beam used in conventional radiation treatment, by its nature each beam destroys healthy tissue on its way to and past the targeted tumor.

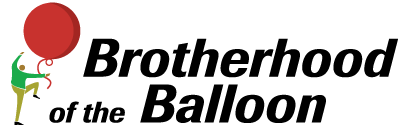

But the sub-atomic particles called protons can be directed to focus only on cancerous tumors, leaving healthy tissue virtually untouched. The proton beam enters the body at a low energy level, then is controlled to increase dramatically just at the site of the cancerous tumor before it dissipates entirely. The point where it reaches its maximum strength is called the Bragg Peak. On a graph it looks like a ski jump.

Fig. 1 shows the path of a single proton. Fig. 2 shows how conventional radiation (red) delivers radiation throughout the body while proton radiation (blue) can be controlled to concentrate its energy on the target tumor alone. (University of Florida Proton Therapy Institute)

Tens of thousands of cancer victims have benefited from this discovery since it was first used to treat cancer patients more than fifty years ago, yet until recently proton beam therapy was described in most medical literature (if at all) as new and experimental. Not at all; it's a proven, mature technology that has been hiding in plain sight for years.

Critics charge that the treatment is too costly, and that prostate cancers can be treated for less money using conventional (photon) radiation, even if more complex cancers can best be treated with protons. They worry that the multimillion dollar construction costs and high price of treatment will drive up the already high price of medical care in the United States.

Furthermore, many radiation oncologists and urologists are unfamiliar with the technology, and often dismiss it as "experimental" or "new-agey," though they are talking about a technology that has been in use for more than sixty years!

One patient was told that if he wanted to go to Loma Linda for proton therapy he should find a new urologist. Another doctor suggested that the many proton patients who express their satisfaction with the treatment are nothing but a "cult." This ignorance will wane as more and more hospitals begin operating proton radiation facilities and curing an impressive number of patients.

Physicians who work with proton radiation therapy and patients who have been treated by it strongly disagree with the skeptics. The advantages of a treatment that destroys the cancer while sparing healthy tissues are obvious and compelling. In the foreword to a 2007 medical textbook on proton therapy, Dr. Herman Suit of the Massachusetts General Hospital says: "any … treatment that achieves a higher radiation dose…to the tumor [than it does to] normal tissues is by definition a superior treatment."

Dr. Jerry Slater, Chief of Radiation Medicine at Loma Linda, says that x-rays can't tell good cells from bad ones, but "with protons, I can always put the beam where I want it."

As for cost, my Loma Linda radiation oncologist told me recently that significant cost reduction "is already beginning to happen. We have started treating many prostate patients with a shorter treatment protocol which does indeed drop the price to the patient and/or the insurer by approximately 50%, to the point that it equals what it would cost the insurer to pay for a standard course of IMRT.

"We are also doing this for some breast and lung patients with the same result. In addition, several of the proton vendors are offering machines and facilities which are less expensive ..."

Loma Linda

I described earlier how I had reached the decision to have my prostate cancer treated by proton radiation at Loma Linda. We were so convinced it was the right course to take that Joy joked: "If you don't want to go there, I'm going to go alone and take your prostate with me!"

Joy and I flew to California in late September 2007. We rented an apartment steps from the hospital, and had our car driven out by an auto delivery company (cheaper than renting one). I met my doctor the next day, had a few tests, and began treatment a week later.

There were 45 days of treatment, five days a week, for nine weeks. Each day's treatment took only a few minutes, only seconds of it involving actual radiation. All of it was covered by Medicare and my Medicare supplementary insurance. We returned home in early December. In the 6-1/2 years since then, I have had only minimal and temporary side effects of any kind. For five years I had a follow-up examination with my urologist every six months, and now check my PSA, which has dropped to a barely detectable level, once a year.

Life After Proton

I have been bitten by the same bug as so many other "proton graduates." I have a never-ending commitment to help others who have been newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. I want to urge them to look seriously into proton beam radiation treatment.

Here is a photo of Tom undergoing his proton treatment at LLUMC.

Updated: December 2015

Eight years out from my radiation vacation at Loma Linda, and my PSA is lower than ever! Now barely detectable and down to 0.14. Joy and I had a tough start to the year 2007, health-wise: she with a series of complicated abdominal operations, and I with the shock of a prostate cancer diagnosis. Her surgeries were totally successful, and my decision to go to Loma Linda for proton radiation (our joint decision; after looking into the alternatives, she said, “If you don’t go to Loma Linda to do this, I’m going there myself and taking your prostate with me!) was — next to marrying such a smart woman — the best one I’d ever made. We both came out of our dual medical experiences feeling reborn.